Abbas Kiarostami

| عباس کیارستمی Abbās Kiyārostamī |

|

|---|---|

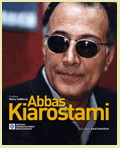

Kiarostami at the 65th Venice Film Festival, 2008 |

|

| Born | 22 June 1940 Tehran, Iran |

| Occupation | Director, screenwriter, producer |

| Years active | 1962–present |

Abbas Kiarostami (Persian: عباس کیارستمی Abbās Kiyārostamī; born 22 June 1940) is an internationally acclaimed Iranian film director, screenwriter, photographer and film producer.[1][2][3] An active filmmaker since 1970, Kiarostami has been involved in over forty films, including shorts and documentaries. Kiarostami attained critical acclaim for directing the Koker trilogy, Taste of Cherry, and The Wind Will Carry Us.

Kiarostami has worked extensively as a screenwriter, film editor, art director and producer and has designed credit titles and publicity material. He is also a poet, photographer, painter, illustrator, and graphic designer.

Kiarostami is part of a generation of filmmakers in the Iranian New Wave, a Persian cinema movement that started in the late 1960s and includes pioneering directors such as Forough Farrokhzad, Sohrab Shahid Saless, Bahram Beizai, and Parviz Kimiavi. The filmmakers share many common techniques including the use of poetic dialogue and allegorical storytelling dealing with political and philosophical issues.[4]

Kiarostami has a reputation for using child protagonists, for documentary style narrative films,[5] for stories that take place in rural villages, and for conversations that unfold inside cars, using stationary mounted cameras. He is also known for his use of contemporary Iranian poetry in the dialogue, titles, and themes of his films.

Contents |

Early life and background

Kiarostami was born in Tehran. His first artistic experience was painting, which he continued into his late teens, winning a painting competition at the age of eighteen shortly before he left home to study at the Tehran University School of Fine Arts.[6] There he majored in painting and graphic design, and supported his degree by working as a traffic policeman. As a painter, designer, and illustrator, Kiarostami worked in advertising in the 1960s, designing posters and creating commercials. Between 1962 and 1966, he shot around 150 advertisements for Iranian television. Towards the late 1960s, he began creating credit titles for films (including Gheysar by Masoud Kimiai) and illustrating children's books.[6][7]

In 1969, Abbas married Parvin Amir-Gholi but later divorced her in 1982; they had two sons, Ahmad (born 1971) and Bahman (1978). At the age of fifteen, Bahman Kiarostami became a director and cinematographer by directing a documentary Journey to the Land of the Traveller in 1993.

Kiarostami was one of the few directors who remained in Iran after the 1979 revolution, when many of his colleagues fled to the west, and he believes that it was one of the most important decisions of his career. He has stated that his permanent base in Iran and his national identity have consolidated his ability as a filmmaker:

When you take a tree that is rooted in the ground, and transfer it from one place to another, the tree will no longer bear fruit. And if it does, the fruit will not be as good as it was in its original place. This is a rule of nature. I think if I had left my country, I would be the same as the tree.-Abbas Kiarostami[8]

Kiarostami frequently appears wearing dark-lensed spectacles or sunglasses. He wears them for medical reasons due to a sensitivity to light.[9]

In 2000, at the San Francisco Film Festival award ceremony, Kiarostami surprised everyone by giving away his Akira Kurosawa Prize for lifetime achievement in directing to veteran Iranian actor Behrooz Vossoughi for his contribution to Iranian Cinema.[10][11]

Film career

1970s

In 1969, when the Iranian New Wave began with Dariush Mehrjui's film Gāv, Kiarostami helped set up a filmmaking department at the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanun) in Tehran. Its debut production and Kiarostami's first film was the twelve-minute The Bread and Alley (1970), a neo-realistic short film about an unfortunate schoolboy's confrontation with an aggressive dog. Breaktime followed in 1972. The department went on to become one of Iran’s most famous film studios, producing not only Kiarostami's films, but acclaimed Persian films such as The Runner and Bashu, the Little Stranger.[6]

In the 1970s, as part of the Iranian cinematic renaissance, Kiarostami pursued an individualistic style of film making.[12] When discussing his first film, he stated:

"Bread and Alley was my first experience in cinema and I must say a very difficult one. I had to work with a very young child, a dog, and an unprofessional crew except for the cinematographer, who was nagging and complaining all the time. Well, the cinematographer, in a sense, was right because I did not follow the conventions of film making that he had become accustomed to."[13]

Following The Experience (1973), Kiarostami released The Traveler (Mossafer) in 1974. The Traveller tells the story of Hassan Darabi, a troublesome, amoral ten-year-old boy in a small Iranian town. He wishes to see the Iran national football team play an important match in Tehran. In order to achieve that, he scams his friends and neighbors. After a number of adventures, he finally reaches Tehran stadium in time for the match. The film addresses the boy's determination in his goal, and his indifference to the effects of his actions on other people, particularly those closest to him. The film is an examination of human behavior and the balance of right and wrong. The film furthered Kiarostami's reputation of realism, diegetic simplicity, and stylistic complexity, as well as showing a fascination with physical and spiritual journeys.[14]

In 1975, Kiarostami directed two short films So Can I and Two Solutions for One Problem. In early 1976, he released Colors, followed by the fifty-four minute film A Wedding Suit, a story about three teenagers coming into conflict over a suit for a wedding.[15][16] Kiarostami's first feature film was the 112-minute Report (1977). It revolved around the life of a tax collector accused of accepting bribes; suicide was among its themes. In 1979, he produced and directed First Case, Second Case.

1980s

In the early 1980s, Kiarostami directed several short films including Dental Hygiene (1980), Orderly or Disorderly (1981), and The Chorus (1982). In 1983, he directed Fellow Citizen, but it was not until 1987 that Abbas began to gain recognition outside of Iran with the release of Where Is the Friend's Home?.

Where Is the Friend's Home? tells a deceptively simple account of a conscientious eight-year-old schoolboy's quest to return his friend's notebook in a neighboring village failing which his friend will be expelled from school. The traditional beliefs of Iranian rural people were depicted throughout the movie. The film has been noted for its poetic use of the Iranian rural landscape and its earnest realism, both important elements of Kiarostami's work. Kiarostami also made the film from a child's point of view, without the condescending tone common to many films about children.[17][18]

Where Is the Friend's Home?, And Life Goes On (1992) (also known as Life and Nothing More), and Through the Olive Trees (1994) are described by critics as the Koker trilogy, because all three films feature the village of Koker in northern Iran. The films are based around the 1990 earthquake disaster in which 50,000 people lost their lives; Kiarostami uses the themes of life, death, change, and continuity to connect the films. The trilogy went on to be become successful in France in the 1990s and other countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany and Finland.[19] However, Kiarostami does not consider the 3 films as part of a trilogy, suggesting instead that the last two titles plus Taste of Cherry (1997) comprise a trilogy, given their common theme — the preciousness of life.[20] In 1987, Kiarostami was involved in the screenwriting of The Key, which he edited but did not direct. In 1989, he released Homework.

1990s

In 1990, Kiarostami directed Close-Up, which narrates the story of the real-life trial of a man who impersonated film-maker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, conning a family into believing they would star in his new film. The family suspects theft as the motive for this charade, but the impersonator, Hossein Sabzian, argues that his motives were more complex. The part documentary, part staged film examines Sabzian's moral justification for usurping Makhmalbaf's identity, questioning his ability to sense his cultural and artistic flair.[21][22] Close-Up received praise from directors such as Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, Jean-Luc Godard, and Nanni Moretti[23] and was released across Europe.[24]

In 1992, Kiarostami directed Life, and Nothing More..., regarded by critics as the second film of the Koker trilogy. The film follows a father and his young son as they drive from Tehran to Koker in search of two young boys who they fear might have perished in the 1990 earthquake. As they travel through the devastated landscape, they meet earthquake survivors forced to carry on with their lives amid tragedy.[25][26][27] That year Kiarostami won a Prix Roberto Rossellini, the first professional film award of his career, for his direction of the film. The last film of the so-called Koker trilogy was Through the Olive Trees (1994), which turns a peripheral scene from Life and Nothing More into the central drama.[28] Critics such as Adrian Martin have called the style of filmmaking in the Koker trilogy as "diagrammatical", linking the zig-zagging patterns in the landscape and the geometry of forces of life and the world.[29][30] A flashback of the zigzag path in Life and Nothing More... (1992) in turn triggers the spectator’s memory of the previous film, Where Is the Friend’s Home? back in 1987, shot before the earthquake. This in turn symbolically links to post-earthquake reconstruction in Through the Olive Trees in 1994.

In 1995, Miramax Films released Through the Olive Trees in the US theatrically.

Kiarostami next wrote the screenplays for The Journey and The White Balloon (1995), for his former assistant Jafar Panahi.[6] Between 1995 and 1996, he was involved in the production of Lumière and Company, a collaboration with 40 other film directors.

In 1997, Kiarostami won the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) award at the Cannes Film Festival for Taste of Cherry,[31] the tale of a desperate man, Mr. Badii, hell-bent on committing suicide. The film involved themes such as morality, the legitimacy of the act of suicide, and the meaning of compassion.[32]

In 1999, Kiarostami directed The Wind Will Carry Us, which won the Grand Jury Prize (Silver Lion) at the Venice International Film Festival. The film contrasted rural and urban views on the dignity of labor, addressing themes of gender equality and the benefits of progress, by means of a stranger's sojourn in a remote Kurdish village.[19] An interesting feature of the movie is that many of the characters are heard but not seen, and there are at least thirteen to fourteen characters in the film who remain invisible throughout.[33]

2000s

In 2002, Kiarostami directed Ten, revealing an unusual method of filmmaking and abandoning many scriptwriting conventions.[33] Kiarostami focused on the socio-political landscape of Iran, and the images are seen through the eyes of one woman as she drives through the streets of Tehran over a period of several days. Her journey is composed of ten conversations with various passengers, which include her sister, a hitchhiking prostitute and a jilted bride and her demanding young son. This style of filmmaking was praised by a number of professional film critics such as A. O. Scott in The New York Times, who wrote that Kiarostami, "in addition to being perhaps the most internationally admired Iranian filmmaker of the past decade, is also among the world masters of automotive cinema...He understands the automobile as a place of reflection, observation and, above all, talk."[34]

In 2001, Kiarostami and his assistant, Seifollah Samadian, traveled to Kampala, Uganda at the request of the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development, to film a documentary about programs assisting Ugandan orphans. He stayed for ten days and made ABC Africa. The trip was originally intended as a research in preparation for the actual filming, but Kiarostami ended up editing the entire film from the video footage obtained.[35] Although Uganda's orphans are overwhelmingly the result of the AIDS epidemic, Time Out editor and National Film Theatre chief programmer Geoff Andrew stated about Kiarostami's film: "Like his previous four features, this film is not about death but life-and-death: how they're linked, and what attitude we might adopt with regard to their symbiotic inevitability."[36]

In 2003, Kiarostami directed Five, a poetic feature with no dialogue or characterization. It consists of five long shots of nature which are single-take sequences, shot with a hand-held DV camera, along the shores of the Caspian Sea. Although the film lacks a clear storyline, Geoff Andrew argues that the film is "more than just pretty pictures". He further adds, "Assembled in order, they comprise a kind of abstract or emotional narrative arc, which moves evocatively from separation and solitude to community, from motion to rest, near-silence to sound and song, light to darkness and back to light again, ending on a note of rebirth and regeneration."[37] He further notes the degree of artifice concealed behind the apparent simplicity of the imagery.

In 2004, Kiarostami produced 10 on Ten, a journal documentary that shares ten lessons on movie-making while driving through the locations of his past films. The movie is shot on digital video with a stationary camera mounted inside the car, in a manner reminiscent of Taste of Cherry and Ten.

In 2005 and 2006, he directed The Roads of Kiarostami, a 32-minute documentary that reflects on the power of landscape, combining austere black-and-white photographs with poetic observations, engaging music with political subject matter.

In 2005 Kiarostami contributed the central section to Tickets, a portmanteau film set on a train traveling through Italy. The other segments were directed by Ken Loach and Ermanno Olmi.

In 2008 he directed the feature Shirin.

2010s

As of April 2010, Kiarostami's next film is Certified Copy which has been shot in Tuscany. It is his first film which has been shot and produced outside Iran. It was entered in competition for the Palme d'Or in the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.

Cinematic style

Individualism

Though Kiarostami has been compared to Satyajit Ray, Vittorio de Sica, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Tati, his films exhibit a singular style, often employing techniques of his own invention.[6]

During the filming of The Bread and Alley in 1970, Kiarostami had major differences with his experienced cinematographer about how to film the boy and the attacking dog. While the cinematographer wanted separate shots of the boy approaching, a close up of his hand as he enters the house and closes the door, followed by a shot of the dog, Kiarostami believed that if the three scenes could be captured as a whole it would have a more profound impact in creating tension over the situation. That one shot took around forty days to complete, until Kiarostami was fully content with the scene. Abbas later commented that the breaking of scenes would have disrupted the rhythm and content of the film's structure, preferring to let the scene flow as one.[13]

Unlike other directors, Kiarostami has showed no interest in staging extravagant combat scenes or complicated chase scenes in large-scale productions, instead attempting to mold the medium of film to his own specifications.[38] Kiarostami appeared to have settled on his style with the Koker trilogy, which included a myriad of references to his own film material, connecting common themes and subject matter between each of the films. Stephen Bransford has contended that Kiarostami's films do not contain references to the work of other directors, but are fashioned in such a manner that they are self-referenced. Bransford believes his films are often fashioned into an ongoing dialectic with one film reflecting on and partially demystifying an earlier film.[28]

Nevertheless, he continued experimenting with new modes of filming, using different directorial methods and techniques. A case in point is Ten, which was filmed in a moving automobile in which Kiarostami was not present. He gave suggestions to the actors about what to do, and a camera placed on the dashboard then filmed them while they drove around Tehran.[13][39] The camera was allowed to roll, capturing the faces of the people involved during their daily routine, using a series of extreme-close shots. Ten was an experiment that used digital cameras to virtually eliminate the director. This new direction towards a Digital-Micro-Cinema, is defined as a micro-budget filmmaking practice, allied with a digital production basis.[40]

Kiarostami's cinema offers a different definition of film. According to film professors such as Jamsheed Akrami of William Paterson University, Kiarostami has consistently attempted to redefine film by lowering its full definition and forcing the increased involvement of the audience. In recent years, he has also progressively trimmed down the timespan of his films, which Akrami believes reduces the filmmaking experience from a collective endeavor to a purer, more basic form of artistic expression.[38]

Fiction and non-fiction

Kiarostami's films contain a notable degree of ambiguity, an unusual mixture of simplicity and complexity, and often a mix of fictional and documentary elements. Kiarostami has stated, "We can never get close to the truth except through lying."[6][41]

The boundary between fiction and non-fiction is significantly reduced in Kiarostami's cinema.[42] The French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, writing about Kiarostami, and in particular Life and Nothing More..., has argued that his films are neither quite fiction nor quite documentary. Life and Nothing More..., he argues, is neither representation nor reportage, but rather "evidence":

[I]t all looks like reporting, but everything underscores (indique à l'évidence) that it is the fiction of a documentary (in fact, Kiarostami shot the film several months after the earthquake), and that it is rather a document about "fiction": not in the sense of imagining the unreal, but in the very specific and precise sense of the technique, of the art of constructing images. For the image by means of which, each time, each opens a world and precedes himself in it (s'y précède) is not pregiven (donnée toute faite) (as are those of dreams, phantasms or bad films): it is to be invented, cut and edited. Thus it is evidence, insofar as, if one day I happen to look at my street on which I walk up and down ten times a day, I construct for an instant a new evidence of my street.[43]

For Jean-Luc Nancy, this notion of cinema as "evidence", rather than as documentary or imagination, is tied to the way Kiarostami deals with life-and-death (cf. the remark by Geoff Andrew on ABC Africa, cited above, to the effect that Kiarostami's films are not about death but about life-and-death):

Existence resists the indifference of life-and-death, it lives beyond mechanical "life," it is always its own mourning, and its own joy. It becomes figure, image. It does not become alienated in images, but it is presented there: the images are the evidence of its existence, the objectivity of its assertion. This thought—which, for me, is the very thought of this film [Life and Nothing More...]—is a difficult thought, perhaps the most difficult. It's a slow thought, always under way, fraying a path so that the path itself becomes thought. It is that which frays images so that images become this thought, so that they become the evidence of this thought—and not in order to "represent" it.[44]

In other words, wanting to accomplish more than just represent life and death as opposing forces, but rather to illustrate the way in which each element of nature is inextricably linked, Kiarostami has devised a cinema that does more than just present the viewer with the documentable "facts," but neither is it simply a matter of artifice. Because "existence" means more than simply life, it is projective, containing an irreducibly fictive element, but in this "being more than" life, it is therefore contaminated by mortality. Nancy is giving a clue, in other words, toward the interpretation of Kiarostami's statement that lying is the only way to truth.[45][46]

Themes of life and death

The concepts of change and continuity, in addition to the themes of life and death, play a major role in Kiarostami's works. In the Koker trilogy, these themes play a central role. As illustrated in the aftermath of the 1990 Tehran earthquake disaster, they represent an ongoing opposition between life and death and the power of human resilience to overcome and defy destruction.

However, unlike the Koker films, which convey an instinctual thirst for survival, Taste of Cherry also explores the fragility of life and rhetorically focuses on the preciousness of life.[20]

In contrast, symbols of death abound in The Wind Will Carry Us with the scenery of graveyard, the imminence of the old woman’s passing, and the ancestors that the character Farzad mentions early in the film. Such devices prompt the viewer to consider the parameters of the afterlife and immaterial existence. The viewer is asked to consider what constitutes the soul, and what happens to it after death. In discussing the film, Kiarostami has stated that he is the person who raises questions, rather than the person who answers them.[47]

Some film critics believe that the assemblage of light versus dark scenes in Kiarostami's film grammar, such as in Taste of Cherry and Wind Will Carry Us, suggests the mutual existence of life with its endless possibilities and death as a factual moment of anyone’s life in his films.[48]

Visual and audio techniques

Kiarostami's style is notable for the use of panoramic long shots, such as in the closing sequences of Life and Nothing More andThrough the Olive Trees, where the audience is intentionally distanced physically from the characters in order to stimulate reflection on their fate. Taste of Cherry is punctuated throughout by shots of this kind, including distant overhead shots of the suicidal Badii's car moving across the hills, usually while he is conversing with a passenger. However, the visual distancing techniques stand in juxtaposition to the sound of the dialog, which always remains in the foreground. Like the coexistence of a private and public space, or the frequent framing of landscapes through car windows, this fusion of distance with proximity can be seen as a way of generating suspense in the most mundane of moments.[26]

This relationship between distance and intimacy, between imagery and sound, is also present in the opening sequence to The Wind Will Carry Us. Michael J. Anderson has argued that such a thematic application of this central concept of presence without presence, through using such techniques, and by often referring to characters which the viewer does not see and sometimes not hear directly affects the nature and concept of space in the geographical framework in which the world is portrayed. Kiarostami's use of sound and imagery conveys a world beyond what is directly visible and/or audible, which Anderson believes emphasizes the interconnectedness and shrinking of time and space in the modern world of telecommunications.[47]

Other commentators such as film critic Ben Zipper believe that Kiarostami’s work as a landscape artist is evident in his compositional distant shots of the dry hills throughout a number of his films directly impacting on his construction on the rural landscapes within his films.[48]

Poetry and imagery

Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak, of the University of Maryland, argues that one aspect of Kiarostami's cinematic style is that he is able to capture the essence of Persian poetry and create poetic imagery within the landscape of his films. In several of his movies such as Where is the Friend's Home and The Wind Will Carry Us, classical Persian poetry is directly quoted in the film, highlighting the artistic link and intimate connection between them. This in turn reflects on the connection between the past and present, between continuity and change.[49]

The characters recite poems mainly from classical Persian poet Omar Khayyám or modern Persian poets such as Sohrab Sepehri and Forough Farrokhzad. One scene in The Wind Will Carry Us has a long shot of a wheat field with rippling golden crops through which the doctor, accompanied by the filmmaker, is riding his scooter in a twisting road. In response to the comment that the other world is a better place than this one, the doctor recites this poem of Khayyam:[48]

| “ | They promise of houries in heaven But I would say wine is better |

” |

However, the aesthetic element involved with the poetry goes much farther back in time and is used more subtly than these examples suggest. Beyond issues of adaptation of text to film, Kiarostami often begins with an insistent will to give visual embodiment to certain specific image-making techniques in Persian poetry, both classical and modern. This prominently results in enunciating a larger philosophical position, namely the ontological oneness of poetry and film.[49]

It has been argued that the creative merit of Kiarostami's adaptation of Sohrab Sepehri and Forough Farrokhzad's poems extends the domain of textual transformation. Adaptation is defined as the transformation of a prior to a new text. Sima Daad of the University of Washington contends that Kiarostami's adaptation arrives at the theoretical realm of adaptation by expanding its limit from inter-textual potential to trans-generic potential.[50]

Spirituality

Kiarostami's films often reflect upon immaterial concepts such as soul and afterlife. At times, however, the very concept of the spiritual seems to be contradicted by the medium itself, given that it has no inherent means to confer the metaphysical. Some film theorists have argued that The Wind Will Carry Us provides a template by which a filmmaker can communicate metaphysical reality. The limits of the frame, the material representation of a space in dialog with another that is not represented, physically become metaphors for the relationship between this world and those which may exist apart from it. By limiting the space of the mise en scène, Kiarostami expands the space of the art.[47]

Kiarostami's "complex" sound-images and philosophical approach have caused frequent comparisons with "mystical" filmmakers such as Andrei Tarkovsky and Robert Bresson. Irrespective of substantial cultural differences, much of western writing about Kiarostami positions him as the Iranian equivalent of such directors, by virtue of universal austere, "spiritual" poetics and moral commitment.[51] Some draw parallels between certain imagery in Kiarostami's films with that of Sufi concepts.[52]

However, differing viewpoints have arisen about this issue. While a vast majority of English-language writers, such as David Sterritt and Spanish film professor Alberto Elena, interpret Kiarostami's films as spiritual films, other critics including David Walsh and Hamish Ford have diminished its influence in his films.[20][51][52]

Filmography

Poetry and photography

Kiarostami, along with Jean Cocteau, Derek Jarman, and Gulzar, is part of a tradition of filmmakers whose artistic expressions are not restricted to one medium, but who show the ability to use other forms such as poetry, set designs, painting, or photography to relate their interpretation of the world we live in and to illustrate their understanding of our preoccupations and identities.[53]

Kiarostami is also a noted photographer and poet. A bilingual collection of more than 200 of his poems, Walking with the Wind, was published by Harvard University Press. His photographic work includes Untitled Photographs, a collection of over thirty photographs, essentially of snow landscapes, taken in his hometown Tehran, between 1978 and 2003. An exhibition of Kiarostami's photographs of roads, trees and views from a car were shown at PS1 Contemporary Art Center in New York in 2007.[54] In 1999, He also published a collection of his poems.[6][55]

Riccardo Zipoli, from the Università Ca' Foscari Venezia in Venice, has examined some aspects of the relations and interconnections between Kiarostami's poems and his films. The results of the analysis reveal how Kiarostami's treatment of this theme is similar in his poems and films.[56] Kiarostami's poetry is reminiscent of the later nature poems of the Persian painter-poet, Sohrab Sepehri. On the other hand, the succinct allusion to philosophical truths without the need for deliberation, the non-judgmental tone of the poetic voice, and the structure of the poem—absence of personal pronouns, adverbs or over reliance on adjectives—as well as the lines containing a kigo (a season word) gives much of this poetry a Haikuesque characteristic.[53]

Reception and criticism

Kiarostami has received worldwide acclaim for his work from both audiences and critics, and, in 1999, he was unequivocally voted the most important film director of the 1990s by two international critics' polls.[57] Four of his films were placed in the top six of Cinematheque Ontario's Best of the '90s poll.[58] He has gained recognition from film theorists, critics, as well as peers such as Jean-Luc Godard, Nanni Moretti (who made a short film about opening one of Kiarostami's films in his theater in Rome), Chris Marker, Ray Carney, and Akira Kurosawa, who said of Kiarostami's films: "Words cannot describe my feelings about them ... When Satyajit Ray passed on, I was very depressed. But after seeing Kiarostami’s films, I thanked God for giving us just the right person to take his place."[6][59] Critically-acclaimed directors such as Martin Scorsese have commented that "Kiarostami represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema."[60] In 2006, The Guardian's panel of critics ranked Kiarostami as the best non-American film director.[61]

Nevertheless, critics such as Jonathan Rosenbaum have argued that "there's no getting around the fact that the movies of Abbas Kiarostami divide audiences—in this country, in his native Iran, and everywhere else they're shown."[26] Rosenbaum argues that disagreements and controversy over Kiarostami's movies have arisen from his style of filmmaking because what in Hollywood would count as essential narrative information is frequently missing from Kiarostami's films. Camera placement, likewise, often defies standard audience expectations. In the closing sequences of Life and Nothing More and Through the Olive Trees, the audience is forced to imagine missing scenes. In Homework and Close-Up, parts of the sound track have been masked, or drop in and out. It has also been argued that the subtlety of Kiarostami's form of cinematic expression is resistant to critical analysis.[62]

While Kiarostami has won significant acclaim in Europe for several of his films, the Iranian government has refused to permit the screening of his films in his native Iran. Kiarostami has responded, "The government has decided not to show any of my films for the past 10 years... I think they don't understand my films and so prevent them being shown just in case there is a message they don't want to get out".[60] Kiarostami has faced opposition in the United States as well. In 2002, he was refused a visa to attend the New York Film Festival in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center.[63][64] Festival director Richard Peña, who had invited him said, "It's a terrible sign of what's happening in my country today that no one seems to realize or care about the kind of negative signal this sends out to the entire Muslim world".[60] Finnish film director Aki Kaurismäki boycotted the festival in protest.[65] Kiarostami had been invited by the New York International Film Festival, as well as Ohio University and Harvard University.[66]

In 2005, London Film School organized a workshop as well as festival of Kiarostami’s work, titled "Abbas Kiarostami: Visions of the Artist". Ben Gibson, Director of the London Film School, said, "Very few people have the creative and intellectual clarity to invent cinema from its most basic elements, from the ground up. We are very lucky to have the chance to see a master like Kiarostami thinking on his feet."[67]

In 2007, The Museum of Modern Art and P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center co-organized a festival of the Kiarostami's work, titled "Abbas Kiarostami: Image Maker".[68] Kiarostami and his cinematic style have been the subject of several books and two films, Il Giorno della prima di Close Up (1996), directed by Nanni Moretti and Abbas Kiarostami: The Art of Living (2003), directed by Fergus Daly. Abbas Kiarostami is also a member of the advisory board of World Cinema Foundation. The project was founded by Martin Scorsese and aimed at finding and reconstructing world cinema films that have been long neglected.[69][70] Austrian director Michael Haneke has admired the work of Abbas Kiarostami as one of the best.[71]

Honors and awards

Kiarostami has won the admiration of audiences and critics worldwide and received at least seventy awards up to the year 2000.[72] Here are some representatives:

- Prix Roberto Rossellini (1992)

- Prix Cine Decouvertes (1992)

- François Truffaut Award (1993)

- Pier Paolo Pasolini Award (1995)

- Federico Fellini Gold Medal, UNESCO (1997)

- Palme d'Or, Cannes Festival (1997)

- Honorary Golden Alexander Prize, Thessaloniki Film Festival (1999)

- Silver Lion, Venice Film Festival (1999)

- Akira Kurosawa Award (2000)

- Honorary doctorate, École Normale Supérieure (2003)

- Konrad Wolf Prize (2003)

- President of the Jury for Caméra d'Or Award, Cannes Festival (2005)

- Fellowship of the British Film Institute (2005)

- Gold Leopard of Honor, Locarno film festival (2005)

- Prix Henri-Langlois Prize (2006)

- Honorary doctorate, University of Toulouse (2007)

- World's great masters, Kolkata Film Festival (2007)

- Glory to the Filmmaker Award, Venice Film Festival (2008)

Film festival work

Kiarostami was a jury member at numerous film festivals, most notably the Cannes Film Festival in 1993, 2002 and 2005. He was also the president of the Caméra d'Or Jury in Cannes Film Festival 2005.

Some representatives:[73][74][75]

- Venice in 1985

- Locarno in 1990

- Cannes in 1993

- San Sebastian in 1996.

- Cannes in 2002

- São Paulo International Film Festival (2004)

- Cannes in 2005 (president)

- Capalbio Cinema Festival in 2007 (president)

Books by Kiarostami

- Abbas Kiarostami, Havres : French translation by Tayebeh Hashemi and Jean-Restom Nasser, ÉRÈS (PO&PSY); Bilingual edition (3 June 2010) ISBN 2749212234.

- Abbas Kiarostami, Abbas Kiarostami: Cahiers du Cinema Livres (24 October 1997) ISBN 2866421965.

- Abbas Kiarostami, Walking with the Wind (Voices and Visions in Film): English translation by Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak and Michael C. Beard, Harvard Film Archive; Bilingual edition (28 February 2002) ISBN 0674008448.

- Abbas Kiarostami, 10 (ten): Cahiers du Cinema Livres (5 September 2002) ISBN 2866423461.

- Abbas Kiarostami, Nahal Tajadod and Jean-Claude Carrière Avec le vent: P.O.L. (5 May 2002) ISBN 2867448891.

- Abbas Kiarostami, Le vent nous emportera: Cahiers du Cinema Livres (5 September 2002) ISBN 286642347X.

- Abbas Kiarostami, La Lettre du Cinema: P.O.L. (12 December 1997) ISBN 2867445892.

See also

- Kiarostami's assistants

- Jafar Panahi

- Hassan Yektapanah

- Bahman Ghobadi

- Bahman Kiarostami (son)

- Elaine Tyler-Hall

- General

- Intellectual movements in Iran

- Iranian New Wave (cinema)

- Cinema of Iran

- List of Iranian intellectuals

Bibliography

- Geoff Andrew, Ten (London: BFI Publishing, 2005).

- Erice-Kiarostami. Correspondences, 2006, ISBN 8496540243, catalogue of an exhibition together with the Spanish filmmaker Víctor Erice

- Alberto Elena, The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami, Saqi Books 2005, ISBN 0-86356-594-8

- Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami (Contemporary Film Directors), University of Illinois Press 2003 (paperback), ISBN 0-252-07111-5

- Jean-Luc Nancy, The Evidence of Film - Abbas Kiarostami, Yves Gevaert, Belgium 2001, ISBN 2-930128-17-8

- Jean-Claude Bernardet, Caminhos de Kiarostami, Melhoramentos; 1 edition (2004), ISBN 978-8535905717

- Marco Dalla Gassa, Abbas Kiarostami, Publisher: Mani (2000) ISBN 978-8880121473

- Youssef Ishaghpour, Le réel, face et pile: Le cinéma d'Abbas Kiarostami , Farrago (2000) ISBN 978-2844900630

- Alberto Barbera and Elisa Resegotti (editors), Kiarostami, Electa (30 April 2004) ISBN 978-8837023904

- Laurent Kretzschmar, "Is Cinema Renewing Itself?", Film-Philosophy. vol. 6 no 15, July 2002.

- Jonathan Rosenbaum, "Lessons from a Master," Chicago Reader, 14 June 1996

References

- ↑ Panel of critics (2003-11-14). "The world's 40 best directors". London: Guardian Unlimited. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2003/nov/14/1. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Karen Simonian (2002). "Abbas Kiarostami Films Featured at Wexner Center" (PDF). Wexner center for the art. http://wexarts.org/info/press/db/87_nr-kiarostami_elec.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ "2002 Ranking for Film Directors". British Film Institute. 2002. http://www.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/63/. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Ivone Margulies (2007). "Abbas Kiarostami". Princeton University. http://etc.princeton.edu/films/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogsection&id=8&Itemid=2. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ "Abbas Kiarostami Biography". Firouzan Film. 2004. http://www.firouzanfilms.com/HallOfFame/Inductees/AbbasKiarostami.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 "Abbas Kiarostami: Biography". Zeitgeist, the spirit of the time. http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/director.php?director_id=33. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Ed Hayes (2002). "10 x Ten: Kiarostami’s journey". Open Democracy. http://www.opendemocracy.net/arts-Film/article_815.jsp. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Jeffries, Stuart (2005-11-29). "Landscapes of the mind". London: Guardian Unlimited. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2005/apr/16/art. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ Ari Siletz (2006). "Besides censorship". iranian.com. http://www.iranian.com/Books/2006/September/Memoir/index.html. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ Judy Stone. "Not Quite a Memoire". Firouzan Films. http://www.firouzanfilms.com/Reviews/BookReviews/AriSiletz_NotQuiteAMemoir.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Jeff Lambert (2000). "43rd Annual San Francisco International Film Festival". Sense of Cinema. http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/festivals/00/7/sfiff.html.

- ↑ Hamid Dabashi (2002). "Notes on Close Up - Iranian Cinema: Past, Present and Future". Strictly Film School. http://www.filmref.com/journal2002.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Shahin Parhami (2004). "A Talk with the Artist: Abbas Kiarostami in Conversation". Synoptique. http://www.synoptique.ca/core/en/articles/kiarostami_interview. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ David Parkinson (2005). "Abbas Kiarostami Season". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/festivals/abbas_kiarostami_2005.shtml. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Chris Payne. "Abbas Kiarostami Masterclass". Channel4. http://www.channel4.com/film/reviews/feature.jsp?id=145506&page=1. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ "Films by Abbas Kiarostami". Stanford University. 1999. http://www.stanford.edu/group/psa/events/1999-00/kiarostami/filmography.utf8.html.

- ↑ Rebecca Flint. "Where Is the friend's home?". World records. http://www.eworldrecords.com/wherisfrienh.html. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ Chris Darke. "Where Is the Friend's Home?" (PDF). Zeitgeistfilms. http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/films/whereisthefriendshome/presskit.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 David Parkinson (2005). "Abbas Kiarostami Season: National Film Theatre, 1st-31 May 2005". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/festivals/abbas_kiarostami_2005.shtml. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Godfrey Cheshire. "Taste of Cherry". The Criterion Collection. http://www.criterion.com/asp/release.asp?id=45&eid=63§ion=essay. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Ed Gonzalez (2002). "Close Up". Slant Magazine. http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/film_review.asp?ID=101.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Anderson (2000). "Close-Up: Holding a Mirror up to the Movies". Combustible Celluloid. http://www.combustiblecelluloid.com/closeup.shtml. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ↑ "Close-Up". Bfi Video Publishing. 1998. http://www.amazon.co.uk/Close-Up-Hossain-Sabzian/dp/B00004CWIZ.

- ↑ Hemangini Gupta (2005). "Celebrating film-making". The Hindu. http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/fr/2005/05/13/stories/2005051303400400.htm.

- ↑ Jeremy Heilman (2002). "Life and Nothing More… (Abbas Kiarostami) 1991". MovieMartyr. http://www.moviemartyr.com/1991/lifeandnothingmore.htm.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Jonathan Rosenbaum (1997). "Fill In The Blanks". Chicago Reader. http://www.chicagoreader.com/movies/archives/1998/0598/05298.html.

- ↑ Film Info. "And Life Goes On (synopsis)". Zeitgeistfilms. http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/film.php?directoryname=andlifegoeson.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Stephen Bransford (2003). "Days in the Country: Representations of Rural Space ...". Sense of Cinema. http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/03/29/kiarostami_rural_space_and_place.html.

- ↑ Maximilian Le Cain. "Kiarostami: The Art of Living". Film Ireland. http://www.filmireland.net/reviews/kiarostami.htm.

- ↑ "Where is the director?". British Film Institute. 2005. http://www.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/issue/200505.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Taste of Cherry". festival-cannes.com. http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/4835/year/1997.html. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ↑ Constantine Santas (2000). "Concepts of Suicide in Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry". Sense of Cinema. http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/9/taste.html.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Geoff Andrew (2005-05-25). "Abbas Kiarostami, interview". London: Guardian Unlimited. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2005/apr/28/hayfilmfestival2005.guardianhayfestival. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ↑ Ten info. "Ten (film) synopsis". Zeitgeistfilms. http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/film.php?directoryname=ten. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Geoff Andrew, Ten (London: BFI Publishing, 2005), p. 35.

- ↑ Geoff Andrew, Ten, (London: BFI Publishing, 2005) p. 32.

- ↑ Geoff Andrew, Ten, (London: BFI Publishing, 2005) pp 73–4.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Jamsheed Akrami (2005). "Cooling Down a 'Hot Medium'". Iran Heritage Foundation. http://www.iranheritage.com/kiarostamiconference/abstracts_full.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Ben Sachs (2003). "With liberty for all: the films of Kiarostami". The Mac Weekley. http://www.macalester.edu/weekly/120503/arts01.html. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ Ganz, A. & Khatib, L. (2006) "Digital Cinema: The transformation of film practice and aesthetics" in New Cinemas, vol. 4 no 1, pp 21–36

- ↑ Adrian Martin (2001). "The White Balloon and Iranian Cinema". Sense of Cinema. http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/01/15/panahi_balloon.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Charles Mudede (1999). "Kiarostami's Genius Style". The Stranger. http://www.thestranger.com/seattle/Content?oid=1802. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Jean-Luc Nancy, "On Evidence: Life and Nothing More, by Abbas Kiarostami," Discourse 21.1 (1999), p.82. Also, cf., Jean Luc Nancy. Is Cinema Renewing Itself? Film-Philosophy. vol. 6 no. 15, July 2002.

- ↑ Jean-Luc Nancy, "On Evidence: Life and Nothing More, by Abbas Kiarostami," Discourse 21.1 (1999), p.85–6.

- ↑ Jean-Luc Nancy, The Evidence of Film - Abbas Kiarostami, Yves Gevaert, Belgium 2001, ISBN 2930128178

- ↑ Injy El-Kashef and Mohamed El-Assyouti (2001). "Strategic lies". Al-Ahram Weekly. http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2001/556/cu1.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Michael J. Anderson (2004). "Beyond Borders". reverse shot. http://www.reverseshot.com/legacy/spring04/wind.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Khatereh Sheibani (2006). "Kiarostami and the Aesthetics of Modern Persian Poetry". Taylor & Francis Group. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/1658991057-83315461/title~content=t713427941~db=all. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Karimi-Hakkak, Ahmad. "From Kinetic Poetics to a Poetic Cinema: Abbas Kiarostami and the Esthetics of Persian Poetry." University of Maryland (2005)

- ↑ Sima Daad (2005). "Adaption, Fidelity, and Transformation: Kiarostami and the Modernist Poetry of Iran". Iran Heritage Foundation. http://www.iranheritage.com/kiarostamiconference/abstracts_full.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Hamish Ford (2005). "The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami by Alberto Elena". Sense of Cinema. http://esvc001106.wic016u.server-web.com/contents/books/06/38/cinema_kiarostami.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Nacim Pak (2005). "Religion and Spirituality in Kiarostami's Works". Iran Heritage Foundation. http://www.iranheritage.org/kiarostamiconference/abstracts_full.htm#j. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Narguess Farzad (2005). "Simplicity and Bliss: Poems of Abbas Kiarostami". Iran Heritage Foundation. http://www.iranheritage.com/kiarostamiconference/abstracts_full.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Iranian Evolution by Ben Davis, Artnet Magazine, Apr. 17, 2007

- ↑ Kiarostami mostra fotos de neve (Kiarostami shows snow photographs) (Portuguese) - a newspaper article on the display of Untitled Photographs in Lisbon.

- ↑ Riccardo Zipoli (2005). "Uncertain Reality: A Topos in Kiarostami's Poems and Films". Iran Heritage Foundation. http://www.iranheritage.org/kiarostamiconference/abstracts_full.htm#n. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Dorna Khazeni (2002). "Close Up: Iranian Cinema Past Present and Future, by Hamid Dabashi.". Brightlightsfilms. http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/35/iraniancinema.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Jason Anderson (2002). "Carried by the wind: Films by Abbas Kiarostami". Eye Weekley. http://www.eyeweekly.com/eye/issue/issue_05.02.02/film/kiarostami.php. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Cynthia Rockwell (2001). "Carney on Cassavetes: Film critic Ray Carney sheds light on the work of legendary indie filmmaker, John Cassavetes.". NEFilm. http://www.newenglandfilm.com/news/archives/01november/carney.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Stuart Jeffries (2005). "Abbas Kiarostami - Not A Martyr". The Guardian. http://www.countercurrents.org/arts-jeffries250405.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Panel of critics (2006). "The world's 40 best directors". London: The Guardian. http://film.guardian.co.uk/features/page/0,11456,1082823,00.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Daniel Ross, Review of Geoff Andrew, Ten.

- ↑ Andrew O'Hehir (2002). "Iran's leading filmmaker denied U.S. visa". Salon.com. http://dir.salon.com/story/ent/movies/2002/09/27/kiarostami/index.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ "Iranian director hands back award". BBC. 2002-10-17. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/film/2321051.stm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Celestine Bohlen (2002). "Abbas Kiarostami Controversy at the 40th NYFF". Human Rights Watch. http://www.hrw.org/iff/2002/kiarostami.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Jacques Mandelbaum (2002). "No entry for Kiarostami". Le Monde. http://www.iranian.com/Arts/2002/September/Kia/index.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ "Abbas Kiarostami workshop 2–10 May 2005". Pars times. 2005. http://www.parstimes.com/film/kiarostami_workshop.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ "Abbas Kiarostami: Image Maker". Museum of Modern Art. 2007. http://www.moma.org/exhibitions/exhibitions.php?id=3955. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ "Martin Scorsese goes global". US today. 2007-05-22. http://www.usatoday.com/life/movies/news/2007-05-22-scorsese_N.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ↑ "Kiarostami joins Scorsese project". PRESS TV. 2007. http://www.presstv.ir/detail.aspx?id=10752§ionid=351020105. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ↑ Wray, John (2007-09-23). "Minister of Fear". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/23/magazine/23haneke-t.html?pagewanted=5&8br. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- ↑ Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa (2002). "Abbas Kiarostami". Sense of Cinema. http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/directors/02/kiarostami.html. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ "Abbas Kiarostami". IndiePix. 2004. http://www2.indiepix.net/creator/creator.pl?id=1503. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ "Abbas Kiarostami". Cannes Film Festival. http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/artist/id/1114.html. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Nick Vivarelli (2007). "Kiarostami to head Capalbio jury". Variety.com. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117966653.html?categoryId=19&cs=1. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

External links

- Abbas Kiarostami at the Internet Movie Database

- Biography of Abbas Kiarostami at Zeitgeist Films

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||